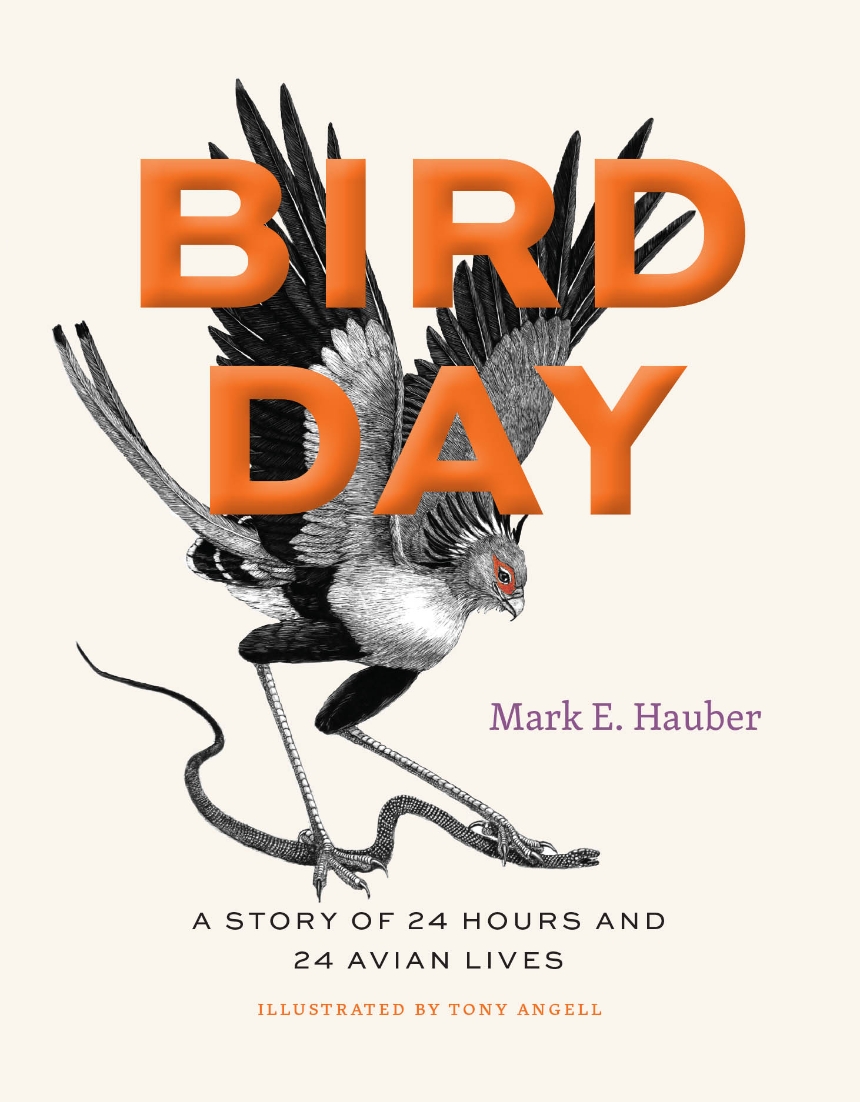

Bird Day

A Story of 24 Hours and 24 Avian Lives

An hourly guide that follows twenty-four birds as they find food, mates, and safety from predators.

From morning to night and from the Antarctic to the equator, birds have busy days. In this short book, ornithologist Mark E. Hauber shows readers exactly how birds spend their time. Each chapter covers a single bird during a single hour, highlighting twenty-four different bird species from around the globe, from the tropics through the temperate zones to the polar regions. We encounter owls and nightjars hunting at night and kiwis and petrels finding their way in the dark. As the sun rises, we witness the beautiful songs of the “dawn chorus.” At eleven o’clock in the morning, we float alongside a common pochard, a duck resting with one eye open to avoid predators. At eight that evening, we spot a hawk swallowing bats whole, gorging on up to fifteen in rapid succession before retreating into the darkness.

For each chapter, award-winning artist Tony Angell has depicted these scenes with his signature pen and ink illustrations, which grow increasingly light and then dark as our bird day passes. Working closely together to narrate and illustrate these unique moments in time, Hauber and Angell have created an engaging read that is a perfect way to spend an hour or two—and a true gift for readers, amateur scientists, and birdwatchers.

From morning to night and from the Antarctic to the equator, birds have busy days. In this short book, ornithologist Mark E. Hauber shows readers exactly how birds spend their time. Each chapter covers a single bird during a single hour, highlighting twenty-four different bird species from around the globe, from the tropics through the temperate zones to the polar regions. We encounter owls and nightjars hunting at night and kiwis and petrels finding their way in the dark. As the sun rises, we witness the beautiful songs of the “dawn chorus.” At eleven o’clock in the morning, we float alongside a common pochard, a duck resting with one eye open to avoid predators. At eight that evening, we spot a hawk swallowing bats whole, gorging on up to fifteen in rapid succession before retreating into the darkness.

For each chapter, award-winning artist Tony Angell has depicted these scenes with his signature pen and ink illustrations, which grow increasingly light and then dark as our bird day passes. Working closely together to narrate and illustrate these unique moments in time, Hauber and Angell have created an engaging read that is a perfect way to spend an hour or two—and a true gift for readers, amateur scientists, and birdwatchers.

See the book trailer on the University of Chicago Press YouTube channel.

168 pages | 24 halftones | 4 3/4 x 6 | © 2023

Biological Sciences: Behavioral Biology, Natural History

Reviews

Table of Contents

Preface

Artist’s Note

Midnight: Barn Owl (Worldwide)

1 AM: Little Spotted Kiwi (New Zealand)

2 AM: Oilbird (South America)

3 AM: Kākāpō (New Zealand)

4 AM: Common Nightingale (Eurasia)

5 AM: Brown-Headed Cowbird (North America)

6 AM (Sunrise): Silvereye (Australasia)

7 AM: Bee Hummingbird (Caribbean)

8 AM: American Robin (North America)

9 AM: Eclectus Parrot (Australasia)

10 AM: Indian Peafowl (Asia, Introduced Worldwide)

11 AM: Common Pochard (Eurasia)

Noon: Ocellated Antbird (Central America)

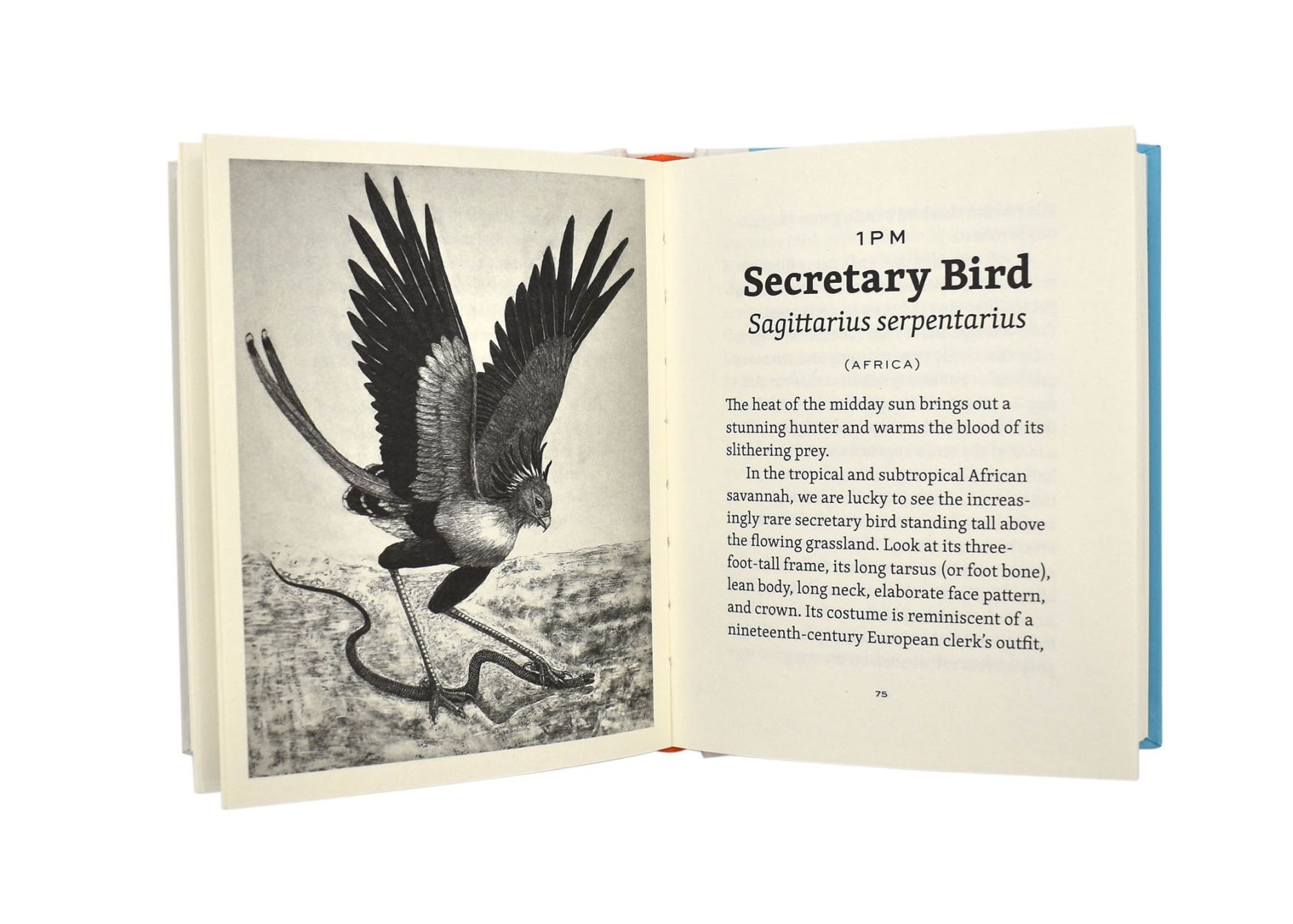

1 PM: Secretary Bird (Africa)

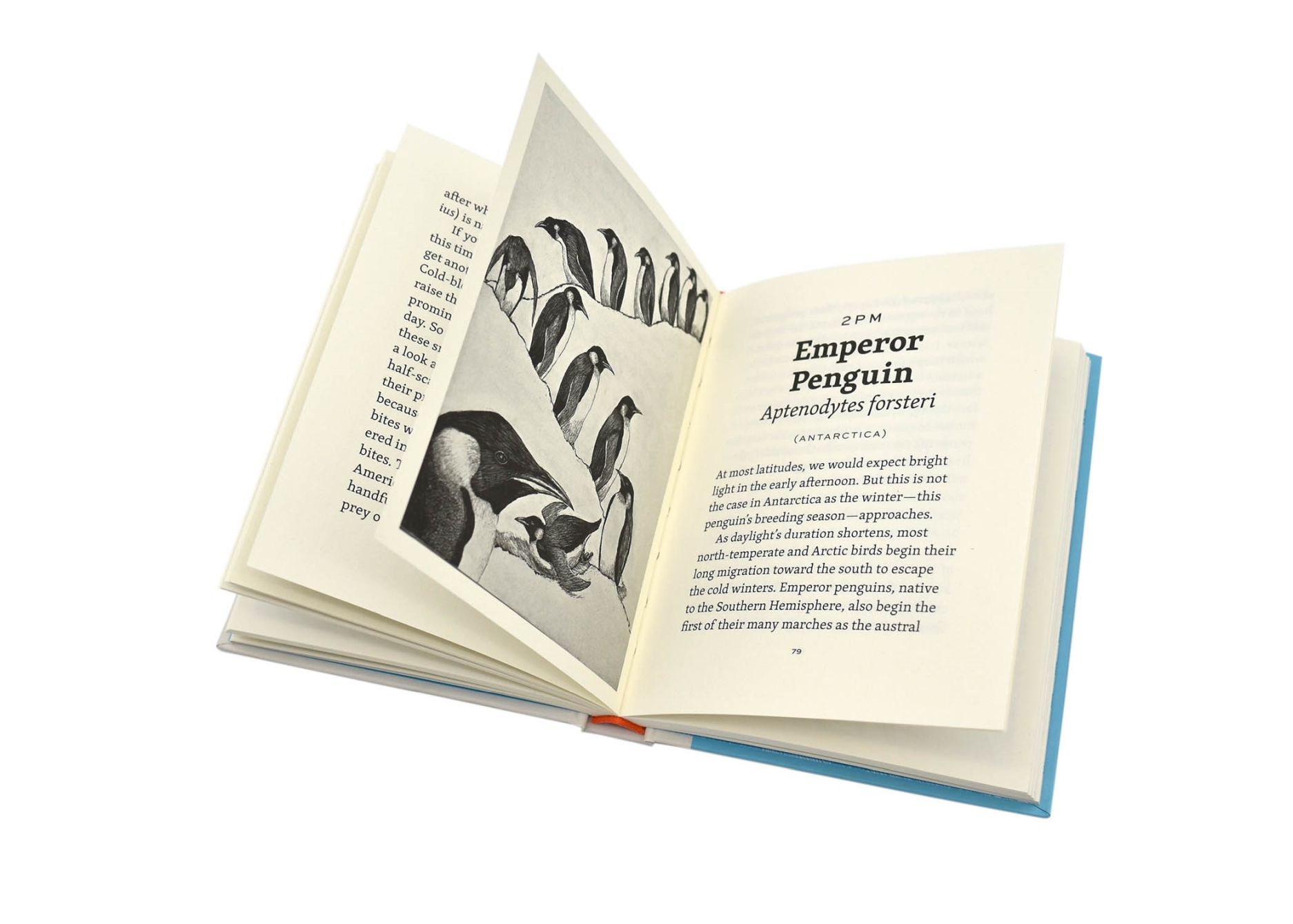

2 PM: Emperor Penguin (Antarctica)

3 PM: Superb Starling (Africa)

4 PM: Common Cuckoo (Eurasia)

5 PM: Indian Myna (Asia, Introduced Worldwide)

6 PM (Sunset): Standard-Winged Nightjar (Africa)

7 PM: Great Snipe (Eurasia)

8 PM: Bat Hawk (Africa and Asia)

9 PM: Black-Crowned Night Heron (Worldwide)

10 PM: Cook’s Petrel (New Zealand)

11 PM: European Robin (Eurasia)

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Further Reading

Index

Artist’s Note

Midnight: Barn Owl (Worldwide)

1 AM: Little Spotted Kiwi (New Zealand)

2 AM: Oilbird (South America)

3 AM: Kākāpō (New Zealand)

4 AM: Common Nightingale (Eurasia)

5 AM: Brown-Headed Cowbird (North America)

6 AM (Sunrise): Silvereye (Australasia)

7 AM: Bee Hummingbird (Caribbean)

8 AM: American Robin (North America)

9 AM: Eclectus Parrot (Australasia)

10 AM: Indian Peafowl (Asia, Introduced Worldwide)

11 AM: Common Pochard (Eurasia)

Noon: Ocellated Antbird (Central America)

1 PM: Secretary Bird (Africa)

2 PM: Emperor Penguin (Antarctica)

3 PM: Superb Starling (Africa)

4 PM: Common Cuckoo (Eurasia)

5 PM: Indian Myna (Asia, Introduced Worldwide)

6 PM (Sunset): Standard-Winged Nightjar (Africa)

7 PM: Great Snipe (Eurasia)

8 PM: Bat Hawk (Africa and Asia)

9 PM: Black-Crowned Night Heron (Worldwide)

10 PM: Cook’s Petrel (New Zealand)

11 PM: European Robin (Eurasia)

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Further Reading

Index

Excerpt

Hearing the scurry of a vole on the forest floor, we see a barn owl emerge from the darkness to catch its prey.

Unless you summer in the Far North or South, midnight represents deep darkness for plants and animals, including humans. Some species certainly embrace the night; they rely on scents, sounds, and even Earth’s magnetic field to find their way. But as most birds depend on sight, you might expect a sleepy, dark start to our bird day. No! Many birds thrive at this time, including owls that have evolved to orient themselves and hunt for their prey in the dimmest of lights. There is perhaps no better example than the barn owl.

Barn owls live pretty much everywhere except Antarctica. But do not take that to mean they are uninteresting. Barn owls can hunt in total darkness. They hear the subtle noises made by voles, mice, rats, and other rodents and can locate them as they rush through the nighttime leaf litter. This requires the owls themselves to be quiet—and they are, flying so silently while hunting that they are able to pick up the softest of sounds from below. Barn owls look relatively large, but their bodies are no bigger or heavier than that of a dove. They are just covered in extra-soft feathers to minimize noise during flight. Large wings and a light body also allow this quieter, slower flight. With these wings, the owls can even hover as they pinpoint their potential prey in the ground cover.

Hearing is one thing, but how do barn owls locate their prey in the dark? Unlike many other owls that have symmetrical ears, the orientation of feathers on the barn owl’s face helps direct sound toward their ears, which are located at different heights. The differing heights help barn owls better perceive subtle changes in the direction and strength of the noises coming from a mouse or vole. This allows them to hear and even create three-dimensional mental maps—matching a sound with the distance to its source, above or below.

Thankfully, tonight is dry. Night rain is the enemy of the barn owl. It dampens their feathers, making flight less quiet, and adds background noise as it falls on the leaf litter, masking the sounds of small mammals scuttering on the ground.

Unless you summer in the Far North or South, midnight represents deep darkness for plants and animals, including humans. Some species certainly embrace the night; they rely on scents, sounds, and even Earth’s magnetic field to find their way. But as most birds depend on sight, you might expect a sleepy, dark start to our bird day. No! Many birds thrive at this time, including owls that have evolved to orient themselves and hunt for their prey in the dimmest of lights. There is perhaps no better example than the barn owl.

Barn owls live pretty much everywhere except Antarctica. But do not take that to mean they are uninteresting. Barn owls can hunt in total darkness. They hear the subtle noises made by voles, mice, rats, and other rodents and can locate them as they rush through the nighttime leaf litter. This requires the owls themselves to be quiet—and they are, flying so silently while hunting that they are able to pick up the softest of sounds from below. Barn owls look relatively large, but their bodies are no bigger or heavier than that of a dove. They are just covered in extra-soft feathers to minimize noise during flight. Large wings and a light body also allow this quieter, slower flight. With these wings, the owls can even hover as they pinpoint their potential prey in the ground cover.

Hearing is one thing, but how do barn owls locate their prey in the dark? Unlike many other owls that have symmetrical ears, the orientation of feathers on the barn owl’s face helps direct sound toward their ears, which are located at different heights. The differing heights help barn owls better perceive subtle changes in the direction and strength of the noises coming from a mouse or vole. This allows them to hear and even create three-dimensional mental maps—matching a sound with the distance to its source, above or below.

Thankfully, tonight is dry. Night rain is the enemy of the barn owl. It dampens their feathers, making flight less quiet, and adds background noise as it falls on the leaf litter, masking the sounds of small mammals scuttering on the ground.