Queer Behavior

Scott Burton and Performance Art

The first book to chart Scott Burton’s performance art and sculpture of the 1970s.

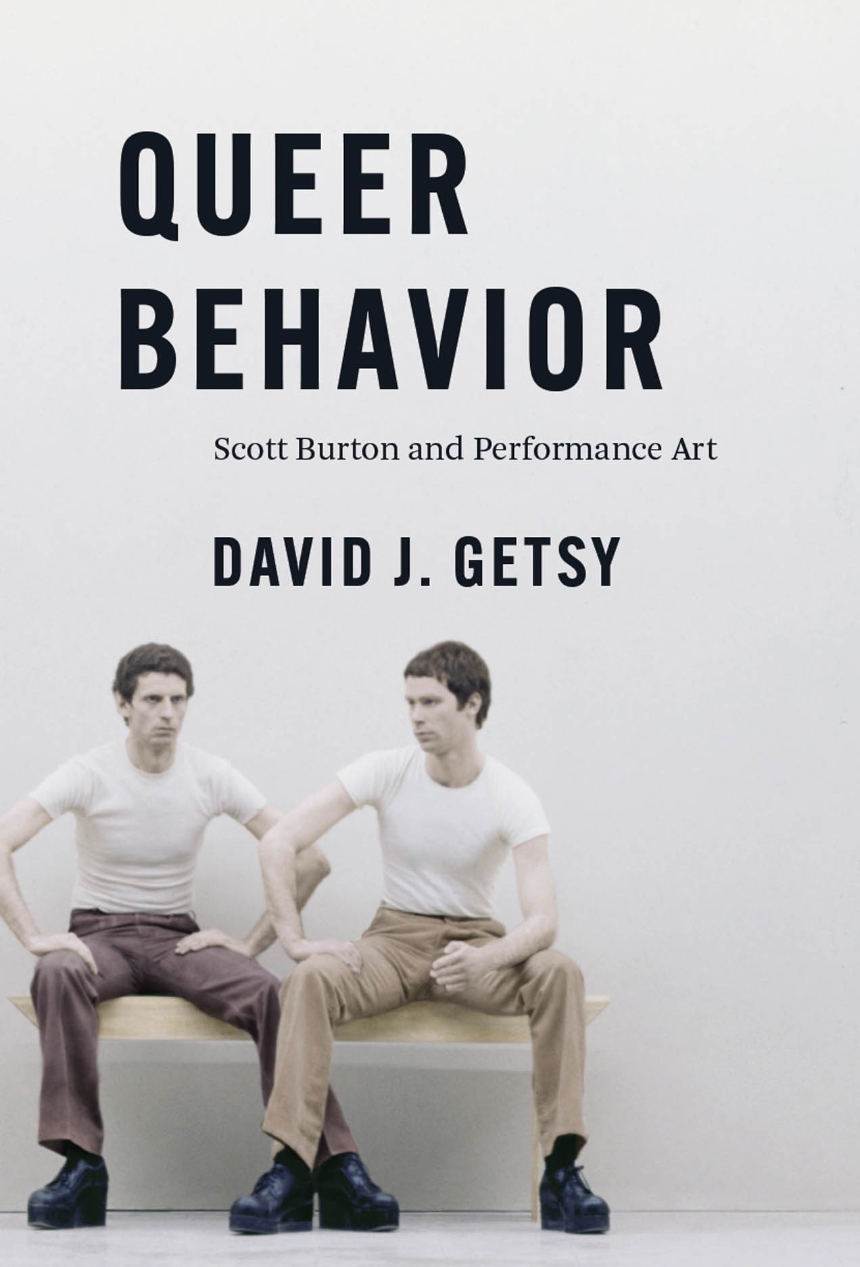

Scott Burton (1939–89) created performance art and sculpture that drew on queer experience and the sexual cultures that flourished in New York City in the 1970s. David J. Getsy argues that Burton looked to body language and queer behavior in public space—most importantly, street cruising—as foundations for rethinking the audiences and possibilities of art. This first book on the artist examines Burton’s underacknowledged contributions to performance art and how he made queer life central in them. Extending his performances about cruising, sexual signaling, and power dynamics throughout the decade, Burton also came to create functional sculptures that covertly signaled queerness by hiding in plain sight as furniture waiting to be used.

With research drawing from multiple archives and numerous interviews, Getsy charts Burton’s deep engagements with postminimalism, performance, feminism, behavioral psychology, design history, and queer culture. A restless and expansive artist, Burton transformed his commitment to gay liberation into a unique practice of performance, sculpture, and public art that aspired to be antielitist, embracing of differences, and open to all. Filled with stories of Burton’s life in New York’s art communities, Queer Behavior makes a case for Burton as one of the most significant out queer artists to emerge in the wake of the Stonewall uprising and offers rich accounts of queer art and performance art in the 1970s.

Scott Burton (1939–89) created performance art and sculpture that drew on queer experience and the sexual cultures that flourished in New York City in the 1970s. David J. Getsy argues that Burton looked to body language and queer behavior in public space—most importantly, street cruising—as foundations for rethinking the audiences and possibilities of art. This first book on the artist examines Burton’s underacknowledged contributions to performance art and how he made queer life central in them. Extending his performances about cruising, sexual signaling, and power dynamics throughout the decade, Burton also came to create functional sculptures that covertly signaled queerness by hiding in plain sight as furniture waiting to be used.

With research drawing from multiple archives and numerous interviews, Getsy charts Burton’s deep engagements with postminimalism, performance, feminism, behavioral psychology, design history, and queer culture. A restless and expansive artist, Burton transformed his commitment to gay liberation into a unique practice of performance, sculpture, and public art that aspired to be antielitist, embracing of differences, and open to all. Filled with stories of Burton’s life in New York’s art communities, Queer Behavior makes a case for Burton as one of the most significant out queer artists to emerge in the wake of the Stonewall uprising and offers rich accounts of queer art and performance art in the 1970s.

Reviews

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Scott Burton’s Queer Postminimalism

Street and Stage: Early Experiments

1. Imitate Ordinary Life: Self-Works, Literalist Theater, and Being Otherwise in Public, 1969–70

2. Languages of the Body: Theatrical, Feminist, and Scientific Foundations, 1970–71

Performance and Its Uses

3. The Emotional Nature of the Number of Inches between Them: Behavior Tableaux, 1972–80

4. Acting Out: Queer Reactions and Reveals, 1973–76

5. Pragmatic Structures: Sculpture and the Performance of Furniture, 1972–79

Conclusion: Homocentric and Demotic

Appendix: List of Performances and Additional Artworks by Scott Burton, 1969–80

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

Introduction: Scott Burton’s Queer Postminimalism

Street and Stage: Early Experiments

1. Imitate Ordinary Life: Self-Works, Literalist Theater, and Being Otherwise in Public, 1969–70

2. Languages of the Body: Theatrical, Feminist, and Scientific Foundations, 1970–71

Performance and Its Uses

3. The Emotional Nature of the Number of Inches between Them: Behavior Tableaux, 1972–80

4. Acting Out: Queer Reactions and Reveals, 1973–76

5. Pragmatic Structures: Sculpture and the Performance of Furniture, 1972–79

Conclusion: Homocentric and Demotic

Appendix: List of Performances and Additional Artworks by Scott Burton, 1969–80

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

Excerpt

Late one night in the summer of 1971, Scott Burton rode his bicycle to Donald Judd’s loft building on Spring Street in Manhattan and hurled a brick through one of its floor- to- ceiling windows. Burton’s close friend Eduardo Costa called the act a “secret art,” but for Burton it wasn’t art. It was rage: “Me and the rock and Donald Judd’s window was pure hatred.” Burton’s postminimalism drew from that same anger, which was not directed solely at Judd but at Minimalism more broadly. He saw in artists like Judd and Carl Andre a profound hypocrisy between their rhetoric and their actions. As Burton’s friend Mac McGinnes recalled, “Scott’s hostility was more towards the posturing of Donald Judd.” In particular, Judd’s acquisition of an entire building in the gentrifying area known as SoHo was, for Burton, a symbol of excess and elitism. “Scott had no tolerance for gentrification,” as Costa explained it. McGinnes agreed: Burton’s visceral act was generated by the visibility of Judd “sitting there gloating in the midst of his own piece.” For Burton, the building was proof of the hollowness of Judd’s claims to have rejected received traditions and to have leveled hierarchies. A few years before the window vandalism, Burton had written that Judd’s sculpture was a “parody of rationality” and that “sometimes this work even seems to mock us.” Judd and others who had been grouped together (however reductively) as “Minimalists” had asserted cold rationality as equitable and open, but Burton saw it as authoritarian and closed.

The exclusiveness Burton disliked in many Minimalists was found not just in the dogma of their formal convictions but also in their performed masculine and heterosexual identities. They had claimed to want to remove the presence of the artist, but in their work— and in their participation in the New York art world— they asserted their experience and their perspective as universal. This left little room for women, artists of color, or openly lesbian or gay artists like Burton. As many argued at the time and after, the neutrality and lack of historical indebtedness claimed by some Minimalists were often tied up in a rhetoric of power and masculinity. Burton recognized this dominance for what it was, and he sought to undermine it. He turned to performance art; he made work that was explicitly about queer sexual cultures; and he lampooned the macho posturing of Minimalist artists like Andre. For Burton, what was needed after Minimalism was a departure from its exclusions, imposed universals, and hierarchies of gender and sexuality.

At the same time, Burton did not wholly reject the ideas that were associated with Minimalism and its moment. Since the mid- 1960s he had been an art critic participating in debates about minimal art and its alternatives. When he started making art in 1969, he pursued central questions that Minimalism raised. He believed that art should embrace fully the radical idea that he saw as its greatest promise: that of the shift from the artist to viewer. He aligned himself with artists who sought to question the universal rather than coldly illustrate it, as he thought Judd did. These artists, who would soon be labeled “postminimalists,” included a contingent of important women artists (such as Lynda Benglis, Hannah Wilke, and Jackie Winsor) who similarly rejected Minimalism’s masculinist universalisms and sought to find a place for difference. Burton identified with this version of the postminimal and with their critical voices. Performance became a way to reconsider the relationship between artist and viewer and, more importantly, to thematize the queer experiences that informed his perspective (and that made him inadmissible in many circles of the New York art world).

It is easily forgotten how few openly lesbian or gay artists there were in the 1970s New York art world, despite the emergence of the gay liberation movement during the decade. As Michael Auping (the curator of Burton’s final performance) reminded me in a conversation, “Scott’s dealing with gay issues was so radical in the 1970s.” There were plenty of lesbian and gay artists in the New York art world, but few made work overtly about their queer experience, and even fewer were allowed to exhibit it in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Burton understood this terrain and made queer performances that infiltrated sanctioned spaces such as the Whitney and Guggenheim Museums. But he also increasingly made work that left no doubt about its queer themes, as when he exhibited a work in 1975 that fantasized about fisting artistic competitor and erstwhile Minimalist Robert Morris “up to the elbow,” as I discuss in chapter 4.

Burton advocated for lesbian and gay artists, and in the mid- 1970s he attempted to organize one of the first compendia of their history (see chapter 4). He drew support from other gay men in his circle of artists and critics, such as Costa, John Perreault, and Robert Pincus- Witten. Of equal importance, however, was the inspiration Burton drew from feminism and the seismic shift it was enacting in the 1970s New York art world. In a 1980 interview, Burton remarked about the conditions of the 1970s: “There are a number of gay dealers and curators and museum directors and a number of gay artists, but absolutely nothing equivalent in the art world— in relation to gay liberation— of the feminist movement which has had a tremendous impact on contemporary art. It changed everything, in the 1970s and all for the better. It was so healthy.” His feminist friends such as Jane Kaufman, Marjorie Strider, Sylvia Sleigh, Wilke, and Linda Nochlin all provided models for how to value difference and critique structural inequities. At a moment when artists were not allowed to foreground queer experience or desire (or were not taken seriously if they did), Burton looked to (and supported) the work of feminism and its denunciation of exclusion. Consequently, his story offers a link between the art histories of feminism and those of gay male artists, often assumed to be unrelated. For Burton, both were allied in their fight against hierarchies and biases operative in the art world— and in society at large.

The exclusiveness Burton disliked in many Minimalists was found not just in the dogma of their formal convictions but also in their performed masculine and heterosexual identities. They had claimed to want to remove the presence of the artist, but in their work— and in their participation in the New York art world— they asserted their experience and their perspective as universal. This left little room for women, artists of color, or openly lesbian or gay artists like Burton. As many argued at the time and after, the neutrality and lack of historical indebtedness claimed by some Minimalists were often tied up in a rhetoric of power and masculinity. Burton recognized this dominance for what it was, and he sought to undermine it. He turned to performance art; he made work that was explicitly about queer sexual cultures; and he lampooned the macho posturing of Minimalist artists like Andre. For Burton, what was needed after Minimalism was a departure from its exclusions, imposed universals, and hierarchies of gender and sexuality.

At the same time, Burton did not wholly reject the ideas that were associated with Minimalism and its moment. Since the mid- 1960s he had been an art critic participating in debates about minimal art and its alternatives. When he started making art in 1969, he pursued central questions that Minimalism raised. He believed that art should embrace fully the radical idea that he saw as its greatest promise: that of the shift from the artist to viewer. He aligned himself with artists who sought to question the universal rather than coldly illustrate it, as he thought Judd did. These artists, who would soon be labeled “postminimalists,” included a contingent of important women artists (such as Lynda Benglis, Hannah Wilke, and Jackie Winsor) who similarly rejected Minimalism’s masculinist universalisms and sought to find a place for difference. Burton identified with this version of the postminimal and with their critical voices. Performance became a way to reconsider the relationship between artist and viewer and, more importantly, to thematize the queer experiences that informed his perspective (and that made him inadmissible in many circles of the New York art world).

It is easily forgotten how few openly lesbian or gay artists there were in the 1970s New York art world, despite the emergence of the gay liberation movement during the decade. As Michael Auping (the curator of Burton’s final performance) reminded me in a conversation, “Scott’s dealing with gay issues was so radical in the 1970s.” There were plenty of lesbian and gay artists in the New York art world, but few made work overtly about their queer experience, and even fewer were allowed to exhibit it in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Burton understood this terrain and made queer performances that infiltrated sanctioned spaces such as the Whitney and Guggenheim Museums. But he also increasingly made work that left no doubt about its queer themes, as when he exhibited a work in 1975 that fantasized about fisting artistic competitor and erstwhile Minimalist Robert Morris “up to the elbow,” as I discuss in chapter 4.

Burton advocated for lesbian and gay artists, and in the mid- 1970s he attempted to organize one of the first compendia of their history (see chapter 4). He drew support from other gay men in his circle of artists and critics, such as Costa, John Perreault, and Robert Pincus- Witten. Of equal importance, however, was the inspiration Burton drew from feminism and the seismic shift it was enacting in the 1970s New York art world. In a 1980 interview, Burton remarked about the conditions of the 1970s: “There are a number of gay dealers and curators and museum directors and a number of gay artists, but absolutely nothing equivalent in the art world— in relation to gay liberation— of the feminist movement which has had a tremendous impact on contemporary art. It changed everything, in the 1970s and all for the better. It was so healthy.” His feminist friends such as Jane Kaufman, Marjorie Strider, Sylvia Sleigh, Wilke, and Linda Nochlin all provided models for how to value difference and critique structural inequities. At a moment when artists were not allowed to foreground queer experience or desire (or were not taken seriously if they did), Burton looked to (and supported) the work of feminism and its denunciation of exclusion. Consequently, his story offers a link between the art histories of feminism and those of gay male artists, often assumed to be unrelated. For Burton, both were allied in their fight against hierarchies and biases operative in the art world— and in society at large.

Awards

National Museum of American Art: Charles C. Eldredge Prize

Shortlist

Dedalus Foundation: Robert Motherwell Book Award

Won