Travels in the Americas

Notes and Impressions of a New World

9780226840024

9780226694955

9780226750408

Travels in the Americas

Notes and Impressions of a New World

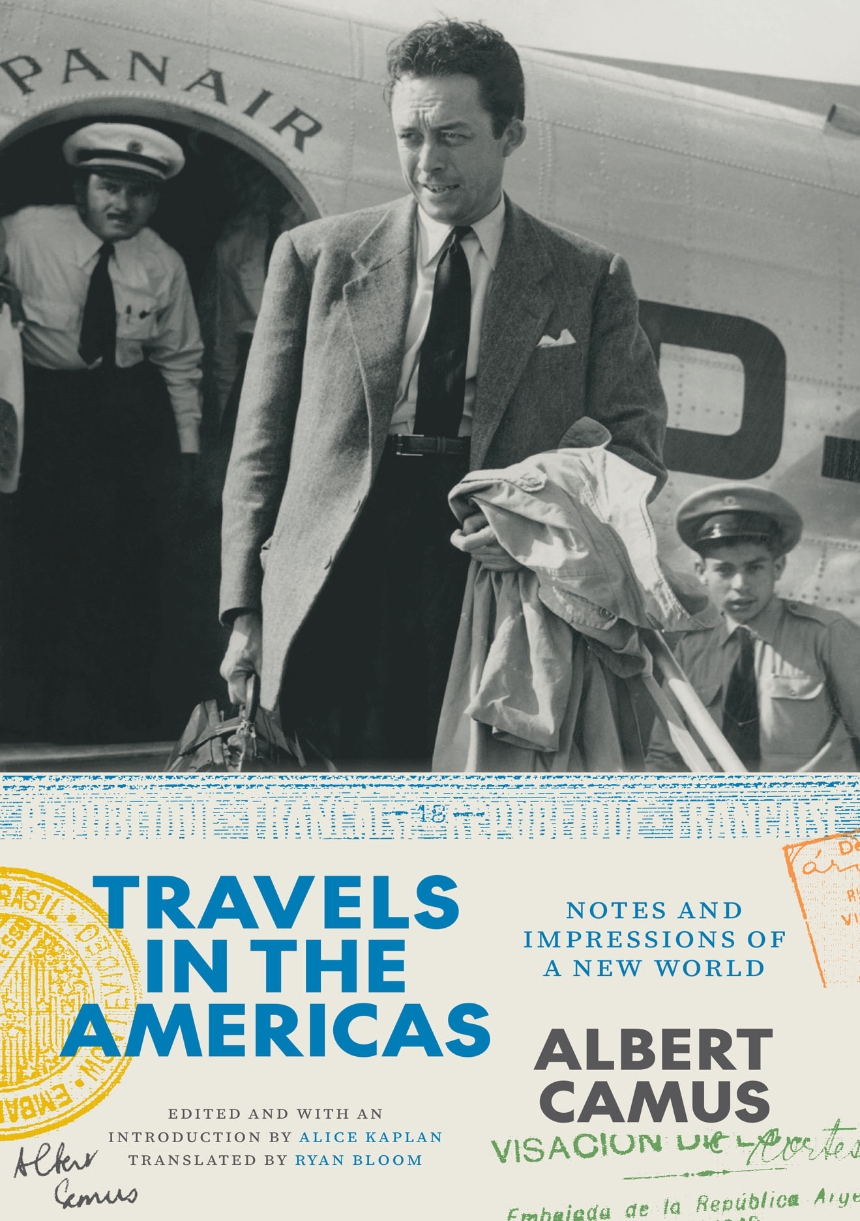

Albert Camus’s lively journals from his eventful visits to the United States and South America in the 1940s, available again in a new translation.

In March 1946, the young Albert Camus crossed from Le Havre to New York. Though he was virtually unknown to American audiences at the time, all that was about to change—The Stranger, his first book translated into English, would soon make him a literary star. By 1949, when he set out on a tour of South America, Camus was an international celebrity. Camus’s journals offer an intimate glimpse into his daily life during these eventful years and showcase his thinking at its most personal—a form of observational writing that the French call choses vues (things seen).

Camus’s journals from these travels record his impressions, frustrations, joys, and longings. Here are his unguarded first impressions of his surroundings and his encounters with publishers, critics, and members of the New York intelligentsia. Long unavailable in English, the journals have now been expertly retranslated by Ryan Bloom, with a new introduction by Alice Kaplan. Bloom’s translation captures the informal, sketch-like quality of Camus’s observations—by turns ironic, bitter, cutting, and melancholy—and the quick notes he must have taken after exhausting days of travel and lecturing. Bloom and Kaplan’s notes and annotations allow readers to walk beside the existentialist thinker as he experiences changes in his own life and the world around him, all in his inimitable style.

In March 1946, the young Albert Camus crossed from Le Havre to New York. Though he was virtually unknown to American audiences at the time, all that was about to change—The Stranger, his first book translated into English, would soon make him a literary star. By 1949, when he set out on a tour of South America, Camus was an international celebrity. Camus’s journals offer an intimate glimpse into his daily life during these eventful years and showcase his thinking at its most personal—a form of observational writing that the French call choses vues (things seen).

Camus’s journals from these travels record his impressions, frustrations, joys, and longings. Here are his unguarded first impressions of his surroundings and his encounters with publishers, critics, and members of the New York intelligentsia. Long unavailable in English, the journals have now been expertly retranslated by Ryan Bloom, with a new introduction by Alice Kaplan. Bloom’s translation captures the informal, sketch-like quality of Camus’s observations—by turns ironic, bitter, cutting, and melancholy—and the quick notes he must have taken after exhausting days of travel and lecturing. Bloom and Kaplan’s notes and annotations allow readers to walk beside the existentialist thinker as he experiences changes in his own life and the world around him, all in his inimitable style.

152 pages | 14 halftones | 5 1/2 x 8 1/2 | © 2023

Literature and Literary Criticism: General Criticism and Critical Theory

Reviews

Excerpt

These two American journals invite us to travel with Albert Camus as he discovers the world and to see the Americas, as if for the first time, through his eyes. The young writer crossed from Le Havre to New York in March 1946, and from Marseille to Dakar to Rio de Janeiro in July 1949. He visited the East Coast of the US and Canada on the first three-month trip, and Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina during an equally long, packed tour of South America. Both North and South American diaries recount his adventures from the time his ship weighs anchor to his return to France. The French have a name for this kind of observational writing: choses vues (things seen). The travel logs are not confessional diaries, yet their gaze outward opens a large window onto the writer’s aspirations and values.

Camus’s world had changed radically from 1946, when he set off to New York in the euphoria of France’s liberation from Nazi occupation, to 1949, when fame and controversy had begun to weigh on him. When he left for New York he was a literary editor at Gallimard. He had made his mark in France as the leading editorialist for Combat, the daily paper that aspired to bring the spirit of the Resistance into the post-war world. The previous fall he had taken a leave from Combat, and he was struggling with revisions of a novel called The Plague, whose final form was eluding him. Though The Stranger was about to be published in English, very few people in the United States knew yet who Camus was. The New York trip marks his beginnings as an international writer. He sat for a Cecil Beaton photo at Vogue, recorded a radio interview with Paul Gilson, was interviewed by Dorothy Norman for her column in the New York Post, and celebrated the launch of The Stranger on the rooftop of the Astor Hotel. He met the cream of the New York intelligentsia and enjoyed the novelty of a half dozen college campuses: Brooklyn College, Penn, Columbia, Bryn Mawr, Harvard, Vassar. By his second transatlantic trip in 1949 he was a far more famous man, known as one of the fashionable French existentialists, despite his impatience with that label, and as the author of The Stranger, The Myth of Sisyphus, and the runaway best seller The Plague, published in 1947. He would no sooner arrive in a new country than he would be blinded by flashbulbs and surrounded by journalists hounding him with questions about how much of an existentialist he really was.

(…)

Like so many other White European modernists of his generation, Camus had absorbed an esthetic fascination with so called “primitive cultures” that seemed to promise an escape from the sins of Europe. And thanks in part to articles by Sartre and Jacques-Laurent Bost, reporting for Combat and Le Figaro in the United States in 1944 and 1945, he was prepared for the postwar spectacle of American racism.

It’s impossible to talk about Camus’s vision of American racism without a detour through his own origins. This child of Algiers had grown up in a poor neighborhood in a colonial city where Muslim citizens were denied basic rights while the signs of a vital Arab culture were written on the cityscape. In the 1930s, he had been part of an artistic movement, “L’école d’Alger,” that wanted to affiliate European Algerian artists with French modernism; they eschewed the condescending, folksy orientalism tendencies of so much colonial art and literature. The Stranger and The Plague, his first two novels, make only the slightest gestures toward the Arab reality of Algiers and Oran. Often dismissed as overly moderate in his views on Algerian nationalism, Camus stayed true to his belief that France needed to reform its colonial policies or lose Algeria. He recruited Muslims for the Communist Party during the brief period of his party membership. He angered the colonial government with his investigative reporting on famine and misery in Kabylia, the mountainous region whose Berber people were often idealized by the French as “noble savages.” In 1945, writing in Combat about the horrific massacre of Muslim veterans in Sétif, Camus was well aware that discontent with colonial crimes had reached a boiling point, that Algerian independence movements were forming. He knew from experience that French resistance to an Algerian nation would be fierce and violent. Camus would remain sensitive to the demands of Algerian nationalists and their critique of colonial injustice, but an Algeria without France was unimaginable to him. He wanted to believe that equal treatment could unite all the diverse peoples of Algeria—that equality and justice would be enough to break the cycle of poverty and violence. So he endorsed a federated Algeria where Berbers, Arabs, Jews, and Europeans could live together and failed to see that such a solution was no longer viable. The tension between his political ideals of freedom from oppression and his European consciousness—his desire for Algeria to remain his country—traveled with him to the Americas.

The new world offered him a less complicated canvas than either France or Algeria. Here he was an outsider who could observe acts of racism, on the one hand, while enjoying African American culture from a safe distance. In New York, he describes a diplomat from French Martinique who had been sent as a matter of course to live in Harlem with other Blacks. It was the man’s first lesson in American racism. Camus duly notes a counterexample: he sees a White man give up his seat on a bus for an old Black woman. The positive example follows the negative, as if Camus needed to believe in the survival of individual acts of dignity in a society where even basic living space was determined by race. Then there is the cultural question. Camus was awed by Maurice Rocco’s boogie-woogie piano playing: “The rhythm, the force, the precision of his playing, the way he puts his whole self into it, jumping, dancing, throwing head and hair right and left.” He has the impression, he writes, “only Negroes give life, passion, and nostalgia to this country that they colonize in their own way.” “Colonize” is a loaded word for an Algerian Frenchman, and it’s hard to know if Camus intends it wishfully or ironically—or both.

Camus’s world had changed radically from 1946, when he set off to New York in the euphoria of France’s liberation from Nazi occupation, to 1949, when fame and controversy had begun to weigh on him. When he left for New York he was a literary editor at Gallimard. He had made his mark in France as the leading editorialist for Combat, the daily paper that aspired to bring the spirit of the Resistance into the post-war world. The previous fall he had taken a leave from Combat, and he was struggling with revisions of a novel called The Plague, whose final form was eluding him. Though The Stranger was about to be published in English, very few people in the United States knew yet who Camus was. The New York trip marks his beginnings as an international writer. He sat for a Cecil Beaton photo at Vogue, recorded a radio interview with Paul Gilson, was interviewed by Dorothy Norman for her column in the New York Post, and celebrated the launch of The Stranger on the rooftop of the Astor Hotel. He met the cream of the New York intelligentsia and enjoyed the novelty of a half dozen college campuses: Brooklyn College, Penn, Columbia, Bryn Mawr, Harvard, Vassar. By his second transatlantic trip in 1949 he was a far more famous man, known as one of the fashionable French existentialists, despite his impatience with that label, and as the author of The Stranger, The Myth of Sisyphus, and the runaway best seller The Plague, published in 1947. He would no sooner arrive in a new country than he would be blinded by flashbulbs and surrounded by journalists hounding him with questions about how much of an existentialist he really was.

(…)

Like so many other White European modernists of his generation, Camus had absorbed an esthetic fascination with so called “primitive cultures” that seemed to promise an escape from the sins of Europe. And thanks in part to articles by Sartre and Jacques-Laurent Bost, reporting for Combat and Le Figaro in the United States in 1944 and 1945, he was prepared for the postwar spectacle of American racism.

It’s impossible to talk about Camus’s vision of American racism without a detour through his own origins. This child of Algiers had grown up in a poor neighborhood in a colonial city where Muslim citizens were denied basic rights while the signs of a vital Arab culture were written on the cityscape. In the 1930s, he had been part of an artistic movement, “L’école d’Alger,” that wanted to affiliate European Algerian artists with French modernism; they eschewed the condescending, folksy orientalism tendencies of so much colonial art and literature. The Stranger and The Plague, his first two novels, make only the slightest gestures toward the Arab reality of Algiers and Oran. Often dismissed as overly moderate in his views on Algerian nationalism, Camus stayed true to his belief that France needed to reform its colonial policies or lose Algeria. He recruited Muslims for the Communist Party during the brief period of his party membership. He angered the colonial government with his investigative reporting on famine and misery in Kabylia, the mountainous region whose Berber people were often idealized by the French as “noble savages.” In 1945, writing in Combat about the horrific massacre of Muslim veterans in Sétif, Camus was well aware that discontent with colonial crimes had reached a boiling point, that Algerian independence movements were forming. He knew from experience that French resistance to an Algerian nation would be fierce and violent. Camus would remain sensitive to the demands of Algerian nationalists and their critique of colonial injustice, but an Algeria without France was unimaginable to him. He wanted to believe that equal treatment could unite all the diverse peoples of Algeria—that equality and justice would be enough to break the cycle of poverty and violence. So he endorsed a federated Algeria where Berbers, Arabs, Jews, and Europeans could live together and failed to see that such a solution was no longer viable. The tension between his political ideals of freedom from oppression and his European consciousness—his desire for Algeria to remain his country—traveled with him to the Americas.

The new world offered him a less complicated canvas than either France or Algeria. Here he was an outsider who could observe acts of racism, on the one hand, while enjoying African American culture from a safe distance. In New York, he describes a diplomat from French Martinique who had been sent as a matter of course to live in Harlem with other Blacks. It was the man’s first lesson in American racism. Camus duly notes a counterexample: he sees a White man give up his seat on a bus for an old Black woman. The positive example follows the negative, as if Camus needed to believe in the survival of individual acts of dignity in a society where even basic living space was determined by race. Then there is the cultural question. Camus was awed by Maurice Rocco’s boogie-woogie piano playing: “The rhythm, the force, the precision of his playing, the way he puts his whole self into it, jumping, dancing, throwing head and hair right and left.” He has the impression, he writes, “only Negroes give life, passion, and nostalgia to this country that they colonize in their own way.” “Colonize” is a loaded word for an Algerian Frenchman, and it’s hard to know if Camus intends it wishfully or ironically—or both.